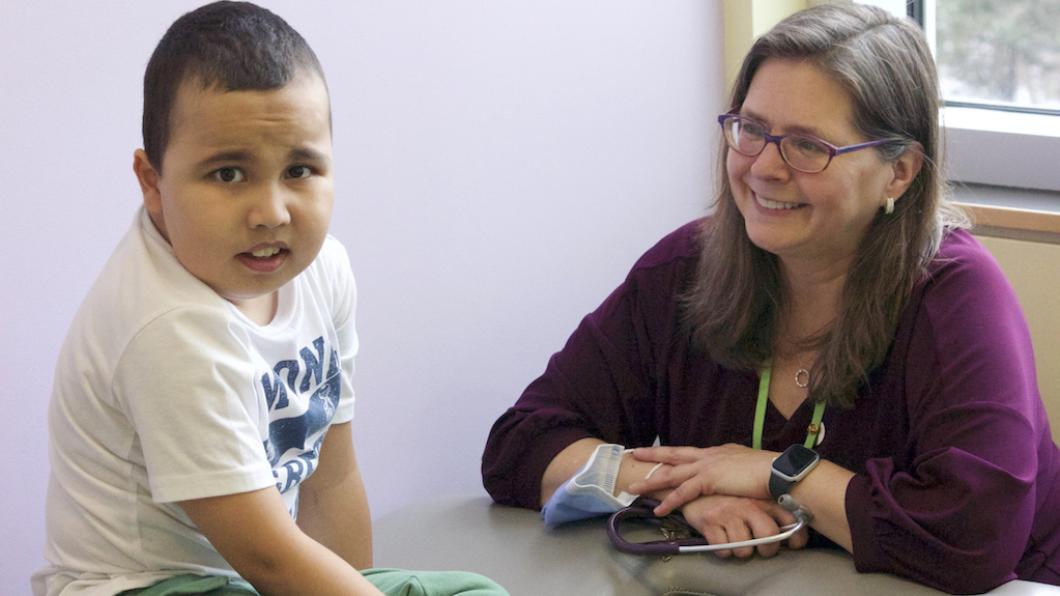

Pediatrician looks for 'moments of connection, happiness and joy'

Photo and story by Louise Kinross

Dr. Laura McAdam says she learned a lesson about how families cope with their child's progressive condition when she attended the wake of a client who died.

"I knew that they loved rollercoasters, but I didn't quite understand how much they loved rollercoasters," says the pediatrician and scientist at Holland Bloorview.

"At the event, they had incredible photographs of all of these really large rollercoasters they had travelled to and ridden on as a family over the years. They also had model rollercoasters they had made on display. The joy in the pictures was incredible, and I learned how important it is to celebrate these day-to-day moments."

Dr. McAdam works with children who have progressive muscle conditions like Duchenne muscular dystrophy and rare genetic disorders like Rett Syndrome. "In clinic, we have a lot of hard conversations," she says. "We talk about losing the ability to walk. We talk about losing the ability to feed yourself. So I try to identify moments of connection, happiness and joy, and to be really thoughtful about, and pay attention, to those moments."

Dr. McAdam works with a multidisciplinary team that includes a medical resident or student; nursing; occupational, physical, recreation and speech therapy; social work; and a youth facilitator who has a disability.

She says her greatest joy is how the team "works with a family to come up with something impactful for that client. It can be linking them with a resource in the community, calling the school to share helpful information, or destigmatizing talking about disability."

Recently, "I got the sense that parents were fearful of talking about their child's disability. When you're noticing physical changes in your child, these can be really hard things to talk about. So when I finished my assessment, I spoke to our social workers and said we need to go back in. We then had a fantastic series of individual conversations with the parents, and then together with the youth. The parents were able to express some of the grief they're feeling and worries they have for the future, and it really shifted things for them."

In clinic, "we always ask the child and family what their priorities are, because what we believe is a priority may not align with how they see things."

The day before, her team rounds on which patients are coming in. The morning of, she reviews these clients with her resident. "I want learners to understand how we interact as a multidisciplinary clinic, and the importance of pre-reading the clinic notes so that they have that history before meeting the family," she says. "Some history lives in the chart and some history lives with the team."

When delivering difficult news Dr. McAdam aims to create a safe space. "Sitting with the family in the moment and giving them permission to express or feel whatever they're feeling, and letting them know it's okay. We can still be strengths-based, but acknowledge that what they're experiencing can be really complex. It's okay to not be okay. When I was new at this job, I probably didn't give enough space for that emotion to occur."

Dr. McAdam values developing relationships with families as their child grows. "I frequently ask parents to brag about their child, so I can understand the child in their natural environment," she says. "When they share something exciting in their child's life, I keep my rehab ears on to see whether we can do anything to remove barriers or expand on that joy."

As a researcher, she has multiple projects on the go. "Some days I see clinical trial patients. We have an ongoing clinical trial looking at a new drug for patients with Duchenne, and are starting another for older patients in their teen years. I have a study looking at bullying in children with neuromuscular conditions where we asked youth about their experiences, and also, with their permission, asked for their parents' perspectives."

Dr. McAdam says with a progressive condition, it can be confusing for peers when they see changes in how a child moves or does things but they don't understand why. "We want to make sure youth voices are heard and they've come up with excellent strategies for what to do with the family and school when a child is bullied." For example, youth suggested parents present to their child's class at the beginning of the year, or whenever their body changes, to explain their condition and accessibility needs and give an opportunity for questions.

"Our goal is to generate an accessible handout on bullying for both youth and families," Dr. McAdam says.

When clinic conversations are emotionally heavy, Dr. McAdam says she debriefs with her team. "We support each other in many ways. And we celebrate the joys in our personal and professional lives, so we know each other as people, not just clinicians."

Balancing her clinical and research work, as well as her role as physician director of ambulatory care, is the greatest challenge, Dr. McAdam says. "Each one of those areas always wants more time than I have available. So it's figuring out the balance. I don't have a good solution for it, other than in my heart I'm a clinician and obviously if families call that is the number one priority. I work with a fantastic, collaborative team, so when one person has a lot on their plate, another person volunteers to help out."

Outside of work, Dr. McAdam manages stress by "connecting with family and friends and doing physical activity. I like nature. I go camping every summer for two weeks of rejuvenation. I try to unplug as much as I can and focus in on nature."

She notes that when she comes to work the sun is usually rising, "so I take a few moments in the parking lot to watch the beautiful colours change and the way the light shines off the clouds. It's a good way to start the day." In good weather she'll take a little walk in the ravine out back during the day.

She uses mindfulness apps that incorporate breathing or visualization exercises to ground herself at work. "I try to be mindful before I go into the clinic, because calmness and mindfulness help me be more observant, and to hear what's being said, and what's not being said, in a room."

Dr. McAdam's connection with Holland Bloorview goes back to when she was part of our summer medical student program. "I worked at both sites when we were on two sites, doing on-call work and seeing inpatients and outpatients. I absolutely loved the experience. One highlight was getting to work with the team and seeing its power. I use the word team in the broadest sense to mean the children and families; teachers and other school staff; and health-care providers, including therapists, physicians and nurses."

The program included a visit with a family in their home. "It had a profound impact on me," she says. "It was eye-opening. It gave me insights I could only glimpse from within the walls of Holland Bloorview. The family was so kind and allowed me to sit in their living room while they shared about their life. It helped me understand their experience and ground me as a physician. That was the start of my journey."

Dr. McAdam says she's enjoyed working with children since "I was a figure skating coach as a kid. During my undergrad at Queen's University I was a volunteer with a Special Olympics program there that's run by occupational and physical therapists. I helped lead it in my fourth year. So a recurring theme was my interest in working with children."

If she could change one thing about children's rehab for the families she supports, it would be "creating accessible recreation in all communities. We see children not just from Toronto but from way up north in Sudbury or Kapuskasing or out in Oshawa or Mississauga. While some communities have all sorts of activities, others don't."

Like this content? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow BLOOM editor @LouiseKinross on X, or @louisekinross.bsky.social on Bluesky, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.