Not everything happens for a reason

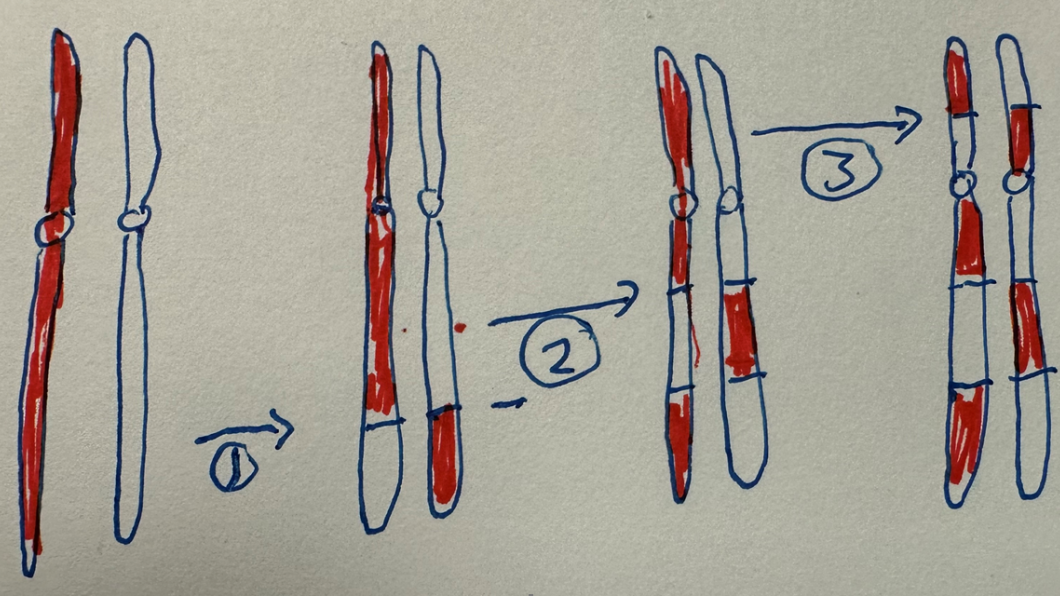

Illustration by Dan Wells, Dean of Natural Sciences and Math, The University of Houston*

By Louise Kinross

A fascinating new book called Fluke argues that randomness plays a much greater role in how the world works than we would like to believe.

“The myth of a controllable world that each of us can tame is ubiquitous, particularly in modern Western society,” writes author Brian Klaas, a professor of global politics at University College London.

Klaas then goes on to show how, in our complex, interconnected world, tiny accidents and arbitrary events can cause massive, unpredictable change.

This caught my attention.

When my son was born with a random genetic condition called Langer-Giedion syndrome (LGS)—a deletion of two genes on the long arm of chromosome 8—the lack of a cause for his condition shook me.

“You have every chance of having a perfect baby—next time,” said the genetics counselor in a cheery voice, reminding me that my husband and I didn’t carry this genetic change. For days, I ruminated: What did “perfect” mean? I now know that it meant non-disabled, or what medicine refers to as “normal.”

Public health messages convey the idea that women control the health of their baby through their actions during pregnancy. What they don’t explain is that we don’t know what causes most birth defects. When pregnant with my second child at age 32, a geneticist advised having an amniocentesis “to prevent having another abnormal baby,” even though the test, at that time, wouldn't identify my son's rare condition.

Having my son relegated to the "abnormal" category in medicine's “normal and abnormal” binary made me feel that I’d failed in some way, and that my son wasn’t valued. Ironically, I had had an amniocentesis that came back “normal” when pregnant with my son with LGS.

Klaas’s book Fluke helped me understand why we assume women have so much control over the health of their unborn child.

The human brain is wired to detect patterns with a simple cause and effect as a way of simplifying our complex world, Klaas writes, and reassuring ourselves that we’re more in control than we really are.

After my son's birth, when our midwife said he had some unusual features, my mind began to swirl. Did something go wrong during the birth? It was a student doctor that delivered him. What about the Prozac I took while pregnant, which had been vetted as okay by the MotherRisk clinic at SickKids Hospital? I felt a wave of terror and self-hatred. Had I done something to hurt my baby?

Days later a geneticist said that he most likely had a genetic condition caused by a random error, a fluke. “It wasn't your fault,” she said. But she didn't tell us how the error happened, or when. In that vacuum, my mind kept switching into overdrive, trying to come up with a predictable storyline. And the guilty character was usually me.

Public health education feeds into mother blame by suggesting women control the health of their baby. For example, How to have a healthy pregnancy and baby at babycenter.com—which is ”doctor approved and evidence based”—lists 11 things to do or not do. The Mayo Clinic offers 5 things you can do to minimize birth defects.

The March of Dimes' logo uses the tagline Healthy Moms, Strong Babies, even though most birth defects have no known cause. If healthy moms mean strong babies, do unhealthy moms cause weak or compromised babies? According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention: “For some birth defects, like fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, we know the cause. But for most birth defects, we don't know what causes them. We think most birth defects are caused by a complex mix of factors, including our genes, our behaviors, and our environment. But, we don't fully understand how these factors might work together to cause birth defects."

Wouldn’t it be more truthful to put the last fact—about not knowing what causes most congenital disabilities—first in public education? If we don’t know what causes most birth defects, the reality is that we can't prevent most of them.

In the late 1990s I started an international association for families affected by LGS with another parent. We had a scientific advisory board, and Dan Wells, a scientist at the University of Houston, was one of our members. Wells had isolated one of the genes affected in LGS.

He explained that the LGS deletion probably occurred during meiosis, a type of cell division in humans that produces egg and sperm cells.

My son is 30 years old now. But it wasn't until I researched this story that I realized that I misunderstood when this cell-division process occurs. I associated it with conception and pregnancy, when it happens before that, potentially long before that.

I reached out to Wells at his old University of Houston e-mail address, hoping he was still there to clarify. He is, but he's now Dean of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

For the last couple of weeks Wells has patiently walked me through a mind-blowing description of how my son ended up with a tiny piece of genetic material missing on chromosome 8.

It happened during “crossing over”—a complex exchange of DNA that occurs during meiosis to promote genetic diversity.

Crossing over happens in a woman when she's a fetus, as women are born with their eggs. If the deletion happened in my egg, it occurred before I was born. I'm not sure why a geneticist never told me this when my son was born. Did the geneticist not know?

In men, crossing over begins with sperm production during puberty. If not ejaculated, sperm stays in a man’s body for about 74 days before being reabsorbed. If the LGS change happened in my husband’s sperm, it happened in about a two-month window before my son’s conception.

Each parent cell has two copies of all chromosomes, Wells says. One from the mother of the parent (grandmother to the eventual child) and one from the father of the parent (grandfather to the eventual child). Yup, you read that right. What you pass on to your children is a mixture of your father's and mother's chromosomes. Isn't that wild?

During meiosis, these 23 paired chromosomes come together to swap maternal and paternal gene variants, before dividing to form cells with only 23 chromosomes each. The LGS deletion is in chromosome number 8.

“Imagine,” Wells says, “the maternal chromosome 8 is a 150-inch green ribbon, and the paternal chromosome 8 is a 150-inch yellow ribbon.”

The two ribbons line up from top to bottom. They then twist around each other, break at the same place, and swap material, “so that one becomes green at the top and yellow at the bottom, and the other becomes yellow at the top and green at the bottom,” Wells says. “This switching of gene variants happens many times at random, creating a green- and yellow-striped ribbon.”

In this way new combinations of genetic code from the child's grandparents are created.

What happens in LGS is called “unequal crossing over”—a rare fluke when a tiny piece of the DNA strand is left out.

With LGS, a two-inch piece of the 150-inch ribbon is missing, Wells says, and the ends reattached. “Chromosome 8 has about 150 million genetic letters, and people with LGS are missing about two million. There are some places in the genome where you could cut out two million letters and it would have an almost unnoticeable effect.” This wasn't one of them.

“There's nothing you or your husband could have done to reduce unequal crossing over," Wells says. He’s told me this many times since we connected in the 1990s, but for some reason, it didn't sink in on an emotional level.

I often felt the finger of blame during medical visits with my son when I was asked to write out a detailed pregnancy history.

I have filled out dozens of these medical forms—answering questions about whether I took prescription or illegal drugs or drank alcohol, had infections or complications, or delivered prematurely—for specialists who should have known that my son's genetic change happened before conception. I have even explained why my pregnancy is irrelevant to my son's disabilities, and asked to skip that section, only to be told that they HAVE TO collect the data anyway. Isn't this absurd?

Which brings me back to Klaas's book Fluke. “We will go to great lengths to invent explanations when none are readily available,” he writes. Wouldn’t that apply to asking mothers of children with random genetic changes to fill out exhaustive pregnancy histories?

When I finally accepted that my son’s condition didn't have an identifiable cause, the knowledge didn’t bring relief. “It was easier to somehow think I had done something than to think that this random error had occurred to my precious child and to us his parents—good people all," I wrote in a blog post. "If I had caused it, there was some kind of control.”

Klaas explains this predilection in his book. The human brain evolved “to be allergic to chance and chaos, wrongly detecting patterns and proposing false reasons for why things happen rather than accepting the accidental or the arbitrary as the correct explanation,” he writes.

Today, I find the idea of randomness freeing. There isn’t a grand plan for how the world works—and there certainly isn’t an equitable one. There wasn’t a reason why my son was born with disabilities. In the same way that there wasn’t a reason I was born without health problems and with so many advantages. I didn’t deserve it, earn it, or do anything special. I was lucky.

An important corollary to the idea of randomness in Klaas's book is the idea of connection. “If you squint at reality for more than a moment, you’ll realize that we’re inextricably linked to one another across time and space,” he writes. “In an intertwined world such as ours, everything we do matters because our ripples can produce storms—or calm them—in the lives of others.”

I think this speaks to how we view disability. Disability isn’t a problem that exists in a person—separate from the community. Disability is a natural part of human variation that exists in families and cultures. Different degrees of interdependence ebb and flow for all of us over a lifetime.

Klaas writes that we are all “part of a unified whole.” Individualism, he says, is a mirage, a delusion. “Connections matter as much as, if not more, than components.”

Complex systems like modern society “involve diverse, interacting and interconnected parts (or individuals) that adapt to one another,” Klaas says. “If you change one aspect of the system, other parts spontaneously adjust creating something altogether new.”

But when we’re talking about disability, adaptation needs to happen at a systems level. Individuals and families can’t do it alone. Design of our built world currently advantages certain bodies and shuts others out. Ableism seeps through our health care and education systems, creating similar disparities there.

Imagine what the world would look like if we chose, as a society, to adapt the environment to the needs of people with disabilities, rather than expecting individuals to change who they are. What if we welcomed people with disabilities, rather than stigmatizing them as abnormal and trying to prevent them?

Klaas talks about how significant the moment of conception is to who we are. “On the day it happens, change any detail—no matter how seemingly insignificant—and you end up with a different child.”

It makes me think about how fragile our existence is, and why each person has value. "It's not just that everything you do matters, but also that it's you, and not someone else, who's doing it," Klaas writes. "Perhaps every one of us creates our own butterfly effect because each of us flaps our wings a little bit differently."

*"I have drawn a crude example of paired chromosomes with three crossover events (1, 2, 3 arrows). For simplicity I have only included one of the red and one of the white chromatids. This illustrates how you get to the 'striped' end product."

Like this content? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow BLOOM Editor @LouiseKinross on Twitter, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.