Are you a special-needs parent? Dream, fail, do it again!

By Louise Kinross

When my son was about two-and-a-half, I called a family support line at Holland Bloorview and the kind voice at the end of the line was June Chiu. I was having trouble finding speech therapy for my son, and June listened, and called me back with some contacts to pursue.

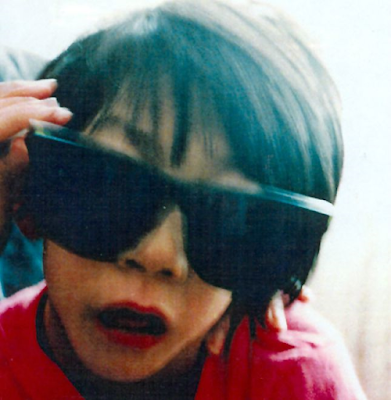

June is an icon at Holland Bloorview. She has worked here for almost 22 years. Before that, June says she “lived” here as her daughter Nadine—aka Dee (above)—received many of our services.

June suggested a workshop for siblings at Holland Bloorview, which she then volunteered to help run. When Dee died at age 11, June had been supporting families in a new role with Family and Community Relations for eight months. June is retiring at the end of this month. I don’t want to write that because I don’t want to believe it’s true. I asked June to share some of what she’s learned over the years.

BLOOM: You had three kids and Dee was your youngest. Tell me about her.

June Chiu: She was a girl who just loved to be with people. She thrived on socializing, music and dancing.

BLOOM: How was she impacted by disability?

June Chiu: She couldn’t do any of those things (June laughs). She didn’t speak. She relied on other people to help her do all the things she would need to do as she grew up.

BLOOM: How did Dee change you as a person?

June Chiu: She really opened my eyes to how different we all are and yet how we can still live a full life, accepting each other for the things that we bring. The other thing I learned was patience. Oh my gosh, patience. Dee’s processing took longer, so you just had to wait. You just had to learn to wait. Life teaches us regularly to hurry, to pack everything in as much as possible. We still do that. But you have to take time in order to make things happen when you have a kid with special needs.

It would be easy to say we don’t have time, we can’t do that. But it’s important we do take time to do those everyday things other families do. Like sitting outside and letting the wind blow in our face. Or gasping for a breath when the wind is really blowing hard. Or sticking your toe in the cold water at the beach. We stuck Dee’s foot in the Atlantic Ocean and the face she made—it was such a shock to her system. But we wanted to do those little things we take so much for granted. To really stop, and do them.

BLOOM: What was your connection to Holland Bloorview?

June Chiu: Initially everyone thought I worked here because we came so often for services and camp. I also volunteered to do a sibling day and some parent information sessions. I approached the director of education services and said ‘I think we need some support here for our families.’ And the person said ‘that’s a great idea, how do we do it?’ I said ‘I’m willing to help’ and I met other parents who also got involved.

BLOOM: What was your thinking about siblings at the time?

June Chiu: As a parent with other children you’re always wondering what can we do to make sure all the children are okay. It’s not only about Dee, it’s about all my kids. We worked with two other parents and we were all thinking the same thing: ‘We know our other kids are okay, but there are times they don’t say things.’ Those sibling days really opened our eyes. I remember one young woman said ‘I know this is going to be my responsibility, but my parents don’t talk to me about it.’ She was 25 years old. That stayed in my brain for so long. Just realizing that no matter what age our children are, there are these hidden feelings. They have this unspoken sense and understanding and as parents we try to say ‘they’re fine’ but are they? Are they okay?

BLOOM: I think the reason many parents aren’t more forthcoming is because they are worried about what degree of responsibility the other children will have in the future. Because most people can’t honestly say that the other siblings won’t have some responsibility, can they?

June Chiu: No, they will have responsibility to varying degrees. You try to put supports in place, to tell them who will be around to help them make decisions. We need some people around who know us as a family and who will grow with us to know what we really want for our kids.We talk about guardianship. You have to know who you want to be your kids’ guardians. It’s the same idea when building a support circle. We were looking for a circle of people who could support us as a family and then be beside the kids as they grew and as they were making decisions and helping to support their sister. Before Dee died, we had started to talk to the kids about that. These are the people we trust and who will help make decisions so you won’t be doing it by yourself.

BLOOM: How would you describe the work you’ve done over the years?

June Chiu: It’s all basically the same—supporting families with information, moral support, encouragement, problem-solving and peer support. I’m a listening ear.

BLOOM: Did you consider not returning to work here after Dee died?

June Chiu: No, it was something I really wanted to do and I saw this huge need. I remember being there as a parent and there was nobody. I met parents from Dee’s nursery school and one woman ventured to create a resource book and that was the book that we parents looked to for all of the information and resources.

BLOOM: What are some of the key things you’ve learned?

June Chiu: I know families have this huge desire to support their kids. They want the best for them and to find something that will help them achieve quality of life. But at the beginning it’s usually a fix-it solution—to help my kid either walk or talk or whatever—those typical things parents want for their children. Then we get so disappointed our child is not achieving those milestones. I don’t know whether it was the doctor who jarred me from the very beginning and destroyed all my hopes.

When Dee was just two months she was in hospital for observation. The doctor said to me, right in front of the nursing station in the hallway: ‘Your child is going to be an infant for a very long time.’ Then she turned and walked away. We read about the ‘shattered glass,’ and that was my shattered glass. But you see even her saying that didn’t give me a picture of what that would be like for Dee.

I did see that she wasn’t reaching her milestones and that the prediction was probably going to be true. And in a way I hope that people could get this news more gently, not having everything destroyed for them. Because if I hadn’t had other people to talk to, and hear from, we wouldn’t have thought about the things we wanted for Dee.

When Dee was five I went to hear two speakers—Ann Turnbull and her son Jay from the United States. Her son’s needs weren’t profound like Dee’s. They talked about Jay living independently and how he could live independently. And I translated that and thought yeah, that could be done. That’s what I want for Dee.That she be able to live somewhere outside, beyond her parents, have a life with friends and family who really love her and have something productive and meaningful to do during the day. That was an ‘aha’ moment for me. I remember turning around after the presentation and saying to Dee’s occupational therapist: ‘That’s exactly what I want for Dee.’ And she looked at me and said ‘Really?’ And I could tell she was thinking ‘Have you gone bonkers woman?’

She didn’t realize that in my head I was already thinking about how that might happen. I was dreaming for Dee and it’s a dream every parent has for their child to live away from their parents. But I knew she’d need help to do that, she couldn’t do that on her own. I was such a dreamer! But I had ideas.

My sense of that developed as I started to listen and find out other stories. In some of my work I was fortunate enough to visit places where people were living in the community interdependently.I remember one situation where a woman needed support 24 hours a day and an agency helped her connect with a single mom with two children who needed housing. The children were in their teens. So this family moved in with this woman and they could do some of the things she needed and they became a family unit. But the agency gave them staffing supports as well.

BLOOM: Without having a lot of money it seems that it would be hard to come up with something innovative like that.

June Chiu: It's not going to happen for everybody. You have to find ways of finding solutions. Today, with the system being so difficult for families to find any support, they really have to start early thinking about what they want for their kids

The three main questions are ‘Where will my kids be living?;’ Who will be around them?;’ and What will they do during the day?' We can’t wait for the system, because the system is not there.

You have to dream. Dreams can also change as you move along, and dreams have incremental steps. You do little steps towards that dream. Dream big. That was a big dream we wanted for Dee, to live interdependently. I remember the look on that OT’s face. It said: ‘She’s really losing it.’ She was thinking how could that be possible? But you problem solve: what are the things you need to make that happen?

I have friends now who are supporting their adult children without disabilities. They’re supporting adult children who've finished school and are out looking for work. They’re paying for their rent. So those differences between supporting a child with disability and a typical child aren’t so different anymore. The gap is narrowing.

BLOOM: How could that help parents in their thinking about what they want for their child with disability?

June Chiu: Maybe we should broaden our thinking as to how we can do things, how we can set up things. We are very private people. We are so afraid to reach out because we don’t want to burden others: ‘This is my burden, I’m not going to burden my other children, my neighbours.’ Maybe it’s the feeling that I should be able to do this myself. Well, heavens no! We cannot do it by ourselves. There is no way. As that saying goes: ‘No man is an island.’

BLOOM: It’s funny, because just recently I approached two neighbours to ask for help. But it was really hard to do that. Because we want to look like we have everything under control. We don’t want people to see our vulnerability.

June Chiu: I remember I wanted Dee to have play dates. She never got an invitation. So I approached women I knew in the neighbourhood and parents of children in her Sunday School class. I didn’t want to have to go to each family individually and talk about this over and over again. I had to build up my nerves. So I practised in front of a mirror. I decided to host a parents’ coffee time. I invited them over, adding that I wanted to talk to them as a group, about our kids.

BLOOM: Did they come?

June Chiu:They came and I had to explain what I was hoping for. It was so scary.‘I want my daughter to have friends, and to have parties to go to,’ I said. The kids were of the age where they still relied on their parents for play dates. ‘I need you to help me’ I said, and they said ‘Oh god, yes.’

They decided they would go home and talk to their kids about it. After that we had a kids’ day. We invited all their kids to a party and it was Dee’s party and the kids came. I had a woman who was an early childhood education specialist facilitate it and it was sort of an education and brainstorming and problem-solving thing. Each of the kids decided on one thing they would do with Dee. And they came up with fabulous ideas: ‘I’ll come over and swing with her on the swing;’ ‘I’m going to bring my turtles over.’ It was all kid stuff and their own thinking.

BLOOM: When I’m sitting here listening to you I can’t help feeling inadequate, that I’ve left so much so late (Louise starts to cry).

June Chiu: It’s really about getting over our fear of reaching out, and look, I’m crying too! We have to practise. Practise in front of the mirror or do it with a friend. And even if you cry in front of the person you’re asking, it’s okay. But we have to learn to let down our guard a little bit and not feel that we always have to be in control. Start reaching out to someone you really know well and who knows you, and who can maybe be your messenger.

We all feel inadequate. That’s why reaching out is so important.I remember one day I lost it in Dee’s nursery school and the coordinator said ‘You finally did it. You’re finally crying.’ Because we always want to be strong.But we all feel inadequate because we feel that we should be doing better. That’s our nature, we’re such high achievers to start with. That’s our downfall.

So give yourself permission to fail, to fall, to cry, and to do it again.

June Chiu (right), with fellow Family Support Specialist Lorraine Thomas, in the Family Resource Centre at Holland Bloorview.