The Therapeutic Clown Program at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital was established by Therapeutic Clowns Canada in 2005.

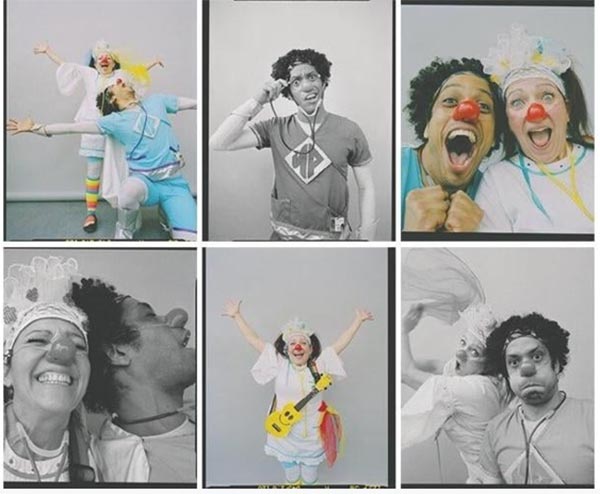

Since its inception it has grown from a solo model therapeutic clown practice to a duo model (i.e. therapeutic clowns working in pairs). The clowns are:

- Nurse Flutter

- Caretaker Piccolo

- Nurse Polo

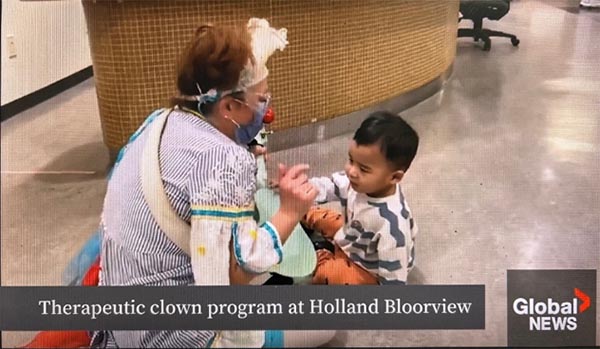

Every Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, the Therapeutic Clowns visit all 3 inpatient units at Holland Bloorview (that is, Brain Injury Rehab, Specialized Orthopedic and Developmental Rehab, and Complex Continuing Care).

The Therapeutic Clown Program offers a diverse range of benefits to Holland Bloorview’s clients. Using skills including music, rhythm, movement, physical comedy and slapstick, providing warmth and laughter to inpatient clients, families and staff.

As with other similar programs, the idea is to always place the client’s needs and desires first. This helps to empower each client and allows them to make choices so they can be the leader of the play interaction.

The clowns also provide positive diversion techniques during certain procedures and assist during various therapy, education and Child Life sessions. The clowns are regarded as living ‘tools’ to be partnered with staff here at Holland Bloorview.

- Complex Continuing Care inpatients

- Specialized Orthopedic and Developmental Rehab inpatients

- Brain Injury Rehab inpatients

- Clinics, families and staff

Blain, S., Kingsnorth, S., Stephens, L., & McKeever, P. (2012). Determining the effects of therapeutic clowning on nurses in a children’s rehabilitation hospital. Arts & Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice, 4(1), 26-38; doi:10.1080/17533015.2011.561359

Kingsnorth, S., Blain, S., & McKeever, P. (2011). Physiological and emotional responses of disabled children to Therapeutic Clowns: A pilot study. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine doi:10.1155/2010/neq008

| Nurse Flutter’s Manager |

| Caretaker Piccolo’s Manager |

| Nurse Polo’s Manager |

Come take a peek at our special display on the 3rd floor (the display cases) by the main elevators, please check it out!

The Therapeutic Clown Team created The Spiral Garden display dedicated to some treasured friends. We wanted to create a space where we can continue to celebrate them in a magical way.

At Holland Bloorview, we have our Spiral Garden in the back of the hospital, which we tried to replicate with beautifully handcrafted miniature pieces like the butterfly bench, the tiny black door on the tree and the spiral path. We added a touch of whimsy and joy.

In our garden, the unique items you see have a special meaning. Take a closer look, as there are many magical little creatures and treasures living in the Spiral Garden display.

Come for a walk and enjoy the garden!

Press and media coverage - highlighting the Therapeutic Clown Program at Holland Bloorview

CTV New’s weekday, evening news broadcast - How one Toronto hospital is using laughter as therapy

By Pauline Chan, health reporter

CTV News Toronto visited CCC client Zachary D’Amico, who has been an inpatient client since October, after contracting a virus that has left the four-year-old with significant muscle weakness. Zach’s parents Lisa and Aldo shared how Holland Bloorview’s therapeutic clowns Nurse Flutter and Caretaker Piccolo have played an important role in their son’s lengthy rehabilitation journey and how the clowns have brought smiles and laughter to the entire family during a difficult time. Capes for Kids, which supports the therapeutic clown program at HB, received a mention in the segment. Also aired on CTV News Channel (national) on March 5.

CityNews’ evening weekday newscast - Clowns bringing joy to kids rehab at Holland Bloorview

By Audra Brown, video journalist

CityNews, the creator of Toronto’s original Speakers Corner booth on Queen. St. West, visited Holland Bloorview’s therapeutic clowns to learn more about “Clown Corner.” The clowns decided to give the beloved Toronto tradition a hilarious re-boot and recently launched the inaugural episode of “Clown Corner” where clients were invited to share a funny joke, advice for other clients or whatever comes to mind. Nurse Flutter and Caretaker Piccolo were interviewed alongside BIRT client Sophia, 10, who was featured in Clown Corner, and shared what the clowns have meant to her during her lengthy inpatient stay. Capes for Kids was also prominently featured in the segment as the therapeutic clown program is funded by donor support.

Duration: 1m43s.

The Therapeutic Clown Program at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital was established in 2005. Therapeutic Clown Practitioners serve to reduce stress, restore a sense of control and dignity through music, rhythm, movement, physical comedy and slapstick providing warmth and laughter to inpatient clients, families and staff. Susan Hay has the story.

CityNews - Therapy clowns providing smiles to patients at Holland Bloorview

By Stella Acquisto and Meredith Bond

Stella Acquisto meets the therapeutic clown team at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital and discusses the benefits of the program.

They say laughter is the best medicine, which seems to be the case at Holland Bloorview Rehabilitation Hospital.

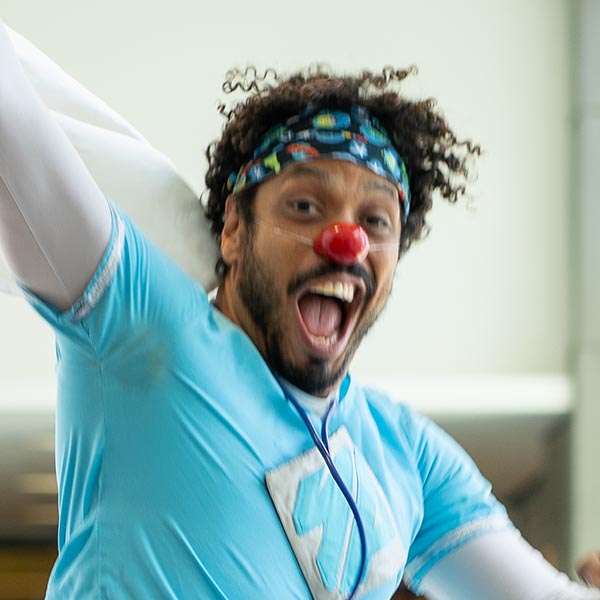

Award-winning performer and former Cirque Du Soliel cast member Suzette Araujo, who goes by Nurse Flutter, and actor/acts educator Leo Dragonieri, also known as Caretaker Piccolo, are two of three “therapeutic clowns” at the rehabilitation centre.

“This is not a show. We are here in service of the clients. They are stars. They are the ones we focus on. It’s about them; they guide the play, [and] they are usually the director,” said Araujo.

“We use tools daily, then we’re on the units, things like improvisation, imaginative play, music, slapstick comedy, here at Holland Bloorview.”

Their role has been integral to the Holland Bloorview care team since 2005.

“It’s not always about humour, often it’s just holding the client’s hand while they’re doing the procedure, you know, or singing a lullaby to an infant who’s been crying we just stay there in silence for a few minutes until they fall asleep,” said Araujo.

“We’re here to provide joy, laughter, and lightness, and we try to find the celebration of the present moment.”

Three days a week, the trio makes their rounds, seeing up to 20 patients per day, with their playful personalities, to reduce the stress of these young patients, especially when they are going through the unimaginable. According to a study published in 2011, therapeutic clowning has been found to have a direct physiological impact on children and a positive effect on their mood and well-being.

“It’s an honour to be in service of others and to use your creativity to help or assist or alleviate anything regarding their journey. Those things are priceless,” added Dragonieri.

On top of performing rounds at the centre, you can find the trio clowning around on Clown TV, an in-house production on YouTube. It was started during the COVID-19 pandemic when they couldn’t be in the room anymore, but it also provided a way for the kids to be involved.

“A lot of those scenes on the Clown TV, the client was the one that directed; it was their idea. We just assisted and worked our way around it; they were the stars again … It was a place for them also to have a creative outlet, a creative voice and to be on television,” explained Araujo.

Araujo said it’s an incredible feeling to bring some joy to these children’s lives.

“It’s a privilege to be with these families and part of their journey. We get to be a part of their memories, and hopefully, we can create fun and magical memories for them … I love what I do.”

Meet Manuel Rodriguez (a.k.a. Nurse Polo) and Suzette Araujo (a.k.a. Nurse Flutter), therepautic clowns at Holland Bloorview, the kids’ rehab hospital in Toronto. “You fall in love with your clients, so it’s really hard when you get bad news,” says Suzette.

By Leah Rumack Special to the Star

“Clowns” may not generally be considered an essential service, but at the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, they definitely are.

Manuel Rodriguez (a.k.a. Nurse Polo) and Suzette Araujo (a.k.a. Nurse Flutter) are the in-house therapeutic clowns at the facility, where you’ll find kids with some of the most complicated health issues in Toronto, including brain injuries, serious damage from accidents and other health challenges, and who therefore require intensive rehab or long-term residential care.

The clowns’ work, which incorporates music, slapstick, singing, dancing and a mega-dose of improv, is considered so important to the wellbeing of the patients that they never stopped working, even during the early days of the pandemic — they just learned to make people laugh while wearing a lot of PPE.

How do you explain therapeutic clowning to people?

Manuel: “A parent once said it best to me: ‘You’re like a big, live toy for the kids to play with.’ We work with the other staff like nurses and physiotherapists a lot. For example, there’s one three-year-old who had a stroke, and we play with him when he rides his therapy bike through the halls. He chases us and we pretend we’re so afraid for our lives in this really silly way, and he has such a blast that he doesn’t even realize he’s going through painful rehab.”

“A parent once said it best to me: ‘You’re like a big, live toy for the kids to play with,’” says Manuel Rodriguez (a.k.a. Nurse Polo).

Do the teenagers ever think they’re too cool for clowns?

Suzette: “We had a 15-year-old with scoliosis who was in a lot of pain. When we introduced ourselves, she mouthed ‘Help me’ to her dad, and we were like ‘This girl is awesome, she has a sense of humour!’ Now she directs us in TikTok dances, and she pretends her shirt has a voice and we have to obey everything it says, like getting locked in her bathroom. She went from ‘help me’ to now she’ll barely let us leave!”

What’s the most challenging part about your job?

Suzette: “We try to find the joyful moments in the present, but you do sometimes fall in love with your clients, so it’s really hard when you get bad news.”

What do you love most about your job?

Manuel: “The child in me wants to play all the time, and therapeutic clowning is completely set up for that — it’s almost therapy for me too.”

Nurse Flutter and Doc Hopper are helping to fight COVID-19 by administering daily doses of laughter.

The therapeutic clowns — otherwise known as Suzzette Araujo and Phil Koole — work at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

Their colleague Greg Vanden Kroonenberg said: "The inpatient children and staff spirits are lifted every time our clowns enter an area. They are joyful, fun and creative."

"During the pandemic, our clowns are required to put on masks and have managed to keep their red noses displayed over them, maintaining their joyful appearance and displaying their playful demeanor at all times!"

In the future, with physical distancing measures in place, they also plan to release a program called Clown TV to ensure they can continue to entertain patients.

The Star - Saluting the Frontlines - Send in the clowns

By Briony Smith Special to the Star

Performing for kids during a pandemic offers unexpected joys.

While medical staff continue to provide care to the children and youth of Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in East York, Doc Hopper and Nurse Flutter are practising another kind of medicine: laughter. At a time when a little levity is needed more than ever, Holland Bloorview’s in-house therapeutic clown practitioners Doc Hopper (a.k.a. Phil Koole) and Nurse Flutter (a.k.a. Suzette Araujo), use music, slapstick and improvisation to boost the mental health of those staying at the hospital, which serves more than 7,500 families each year.

Ridiculous fake deliveries cause chuckles in reserved teens, and a ukelele lures even the shyest clients out of their rooms. “It’s our hope that through humour, passion and emotional expression, we can connect with each other” says Araujo. A Cirque du Soleil alum, Araujo has been with the hospital for more than four years; Koole joined a year and a half ago after stints on the stage. Koole was drawn to working in a hospital because, “the clown is the ultimate servant, and I wanted to put that into practice with those most vulnerable and see if the connections I made might alter their outlook on life.” Koole remembers an immense feeling of heaviness in the wards when the pandemic shutdowns began. But once he and Araujo scrubbed in, masked up and started to perform, “we noticed a shift in the mood,” says Koole. One of their regulars, a non-verbal teen girl, had been lying in bed, unusually reluctant to join in the fun, when she slowly sat up and started grooving to the music, smiling and clapping. A parent, face usually contorted in sadness, started to laugh. The staff felt better, too. Later that day, the clowns received e-mails from fellow hospital employees, thanking the clowns for making their day a little more fun. “We knew then that our clown service was going to be essential during these times, and we continue to experience more and more of these moments,” Araujo says.

Performing during a pandemic has, however, required a few tweaks to the clowns’ normal routines. They can’t get up close and personal with the kids, and any interaction has to happen with social distance. “This really affects our play with children that need that physical connection, and has changed the way we approach each interaction,” Araujo says. Younger kids can sometimes be playfully impulsive pre-pandemic, this was fun, but with physical distancing rules, “it requires more attention and direction, which can change the dynamic of the play” explains Koole.

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is now even more important, adding extra prep time for the comedy duo ahead of their visits. Koole’s “very sweet” girlfriend sewed him some masks to wear during his TTC commute, so he could reserve the precious PPE for use inside the hospital. As for the clowns’ own mental health, Koole says that the risk factor associated with simply leaving the house does lead to a heavier day. “Being a therapeutic clown is an emotional job, and the palpable anxiety surrounding COVID-19 adds weight to that, which has affected me.”

Thankfully the comedy duo works three days a week, leaving some time to rebuild mentally. Araujo’s husband also works in essential service, making negotiating care and education for their child more difficult. “As a clown, being present with lightness and joy is essential. And during these perilous times, that has been challenging for both of us.” Still, the show must go on—but it’s a little easier when there’s two people on the call-sheet. “Thankfully,” Araujo says, “we have each other as clown partners.”

Working as a pair is the best practice in the world of therapeutic clown work. “Working as a duo [allows us] to better support each other and better serve the clients,” according to Koole. “During the pandemic, it’s been even more imperative as we lean on each other to make it through this difficult time.” Plus, they have another ally they can count on as well: their audience. “They make us laugh during our clown play with them, and that brings our spirits up to help perform better,” says Koole.

Bloom - Therapeutic clowns stir unresponsive children

In the first study to measure the long-term physiological effect of therapeutic clowns on hospitalized children, Canadian researchers show that even a child in a vegetative state and those with profound disabilities respond to the red-nosed performers with changes in skin temperature, sweat level and heart and breathing rate.

“Every child showed a physiological response to the clowns that they didn’t show when watching television, and this included children who can’t express themselves verbally or through movement and who appear to be non-responsive,” says lead author Shauna Kingsnorth, a postdoctoral fellow at Bloorview Kids Rehab. Research shows that changes in body signals are reliable indicators of emotional states.

The study was published February 4 online in Evidence-based Alternative and Complementary Medicine.

The scientists measured physiological arousal, emotion and behavior in eight inpatients at Bloorview over four days. Their conditions included severe cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury and brainstem stroke. Velcro bands worn around the children’s fingers measured skin temperature, sweat level and heart rate, and a belt around the chest tracked breathing.

On two of the four days, the scientists measured the children’s reaction to watching 10 minutes of a television show. “Television was a good comparison because the TV is noisy and colorful, like the clowns,” says Stefanie Blain, a PhD biomedical engineering student at Bloorview and co-author of the study. On alternate days, researchers tracked the children’s response to 10-minute visits with Ricky and Dr. Flap (above) – two clowns who engage them with physical and emotional comedy and music, letting the kids direct the action as a means of empowering them.

Five of the eight youth – aged four to 21 – could speak, express emotion through facial expressions and point; two were non-verbal but could show facial emotion; and one child was non-verbal and unable to gesture or use facial expression.

“The physiological data was our main assessment tool and allowed us to include children with profound disabilities who are generally left out of research,” Kingsnorth says. “But we augmented this information with observed information – documenting the frequency of typical expressions of emotion such as smiling, laughing, crying and grimacing – and asking children who could speak to identify their mood by talking about, or pointing to, a card with a face that best depicted how they were feeling.” At the end of the four-day study, children who were verbal participated in a brief interview.

“Most exciting was that every child showed a unique physiological change with the clowns,” Kingsnorth says. “With one child who wasn’t verbal or physically expressive, the research assistant was sure he had been asleep the entire time. But then Stefanie downloaded the physiological data and came running over just about to cry, and you could see how much the child was responding.”

Children’s skin, heart and breathing signals were pulled more frequently out of resting states or the pattern of the four signals changed when the children visited with the clowns. “They’re subtle cues that can’t be picked up by the eye and demonstrate that clowning has a direct effect,” Kingsnorth says.

But what happy or sad looks like physiologically in one child may be different in another, and more research is needed to decode the signals in children who can’t corroborate how they’re feeling through behaviour or speech.

The study began because the therapeutic clowns at Bloorview wanted a way to evaluate their work with children who couldn’t give feedback in conventional ways.

Study results from participants who could report or show their feelings included significant increases in smiling and laughing and decreases in grimacing when interacting with the clowns, as opposed to watching television. Children who could speak showed a positive change in mood following their time with the clowns and no change in mood following television viewing.

The findings suggest therapeutic clowning has a direct, positive impact on hospitalized children – including those with profound disabilities – “and provide hard evidence to support its funding,” Blain says.

The researchers say physiological tracking is a tool that can be used to evaluate a variety of arts interventions for children with disabilities who can’t express themselves in traditional ways. “In future, if we can identify positive and negative physiological responses, we can use that information to create stimulating environments for children who can’t overtly tell us what they like,” Blain says.