'This is the best place to be and the hardest place to leave'

By Louise Kinross

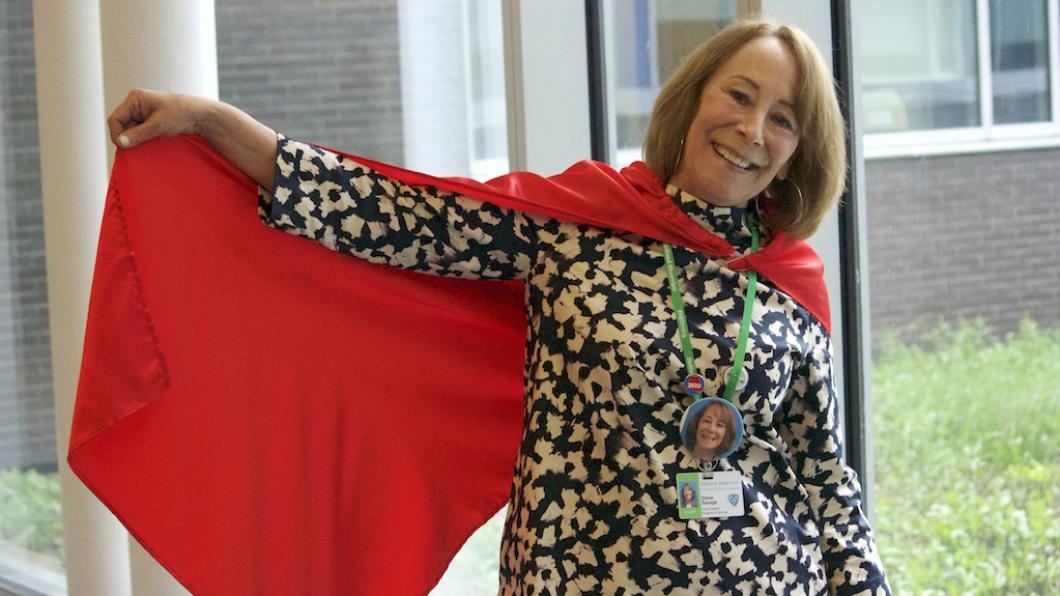

Diane Savage is retiring in June after 12 years at Holland Bloorview. Her roles have included senior director in participation and vice-president of programs and services. She's now vice-president of experience and transformation, leading critical hospital teams to provide high quality, safe care while staying true to her social work roots: "I am always a social worker in my mind," she says, "listening for complexity in people's lives, in the stories that they have been born into and the stories that are told about them." Diane has a passion for coaching, and draws on eclectic sources from The Toronto Raptors to Second City improv. She's already pencilled in a post-retirement course in comedy script writing. We spoke about her 40-year career, which began in Detroit, Michigan, and why she sees one of her leadership roles as "[easing] that burden of self-expectation, of perfection, because perfection isn't the goal."

BLOOM: How did you get into social work?

Diane Savage: My parents were very involved in volunteer work and we had a strong sense of community and contribution, so I was sure I was destined for something like social work. While doing my undergrad I did a co-op placement in an autism program and fell in love with the three social workers who oversaw the program.

I saw their level of skill, compassion and how they related to children who had very, very complex needs and their families. I got to see in action the role of their training, the way their heart also had a place in the work they did, and the way they communicated acceptance and value for the lives of the children they were serving. I came away with the belief that I wanted to be able to contribute in those ways.

I enrolled in graduate social work school in Michigan and had two transformative placement experiences. One was in child protection services in Detroit and the other was in a children's psychiatric unit in a hospital.

BLOOM: How does your background in social work inform how you work as a senior leader in our hospital?

Diane Savage: I love that question. Everybody who knows me knows that I say there isn't a day I wake up and I'm not grateful for having chosen the profession of social work.

I am always a social worker in my mind, listening for complexity in people's lives—in the stories that they have been born into and the stories that are told about them. I think my social work background has inscribed in me an accountability for the whole and to ask better questions.

I bring a system lens to everything that I do. That can make life a little complicated, but I think it helps me be fully present, to check our natural tendency to judge what we're hearing, and it certainly inscribes in me an appreciation for how our experiences shape outcomes.

I grew up in New York in a town called Poughkeepsie, at the foot of the Hudson Valley surrounded by mountains. That geographic environment gave me a perspective on my place in the world.

I went to school in Michigan and worked there and then I met my husband, John, who was Canadian, at a family wedding. We dated back and forth with him living in Toronto while I was in Detroit, and then we decided on Toronto and never ever looked back.

BLOOM: What is a typical work day like?

Diane Savage: It's supporting the work in the portfolio I am privileged to have, which includes Quality, Safety, Risk and Performance, Client and Family Integrated Care, Transitions, Employment and Community Programs, and Collaborative Practice.

We have great leads and great teams. My role is to make sure the leads have the resources they need to support their staff, and the opportunity for a safe space to problem solve and think out loud and be creative. I want them to think big. I'm someone who tends to say 'yes' most of the time, and let's figure out how we'll make it work. That's a deliberate thing, because people come with great ideas. So it's supporting their ideas and trying to open doors and remove barriers to make innovation happen.

My second role is to make sure I'm an impactful member at the senior management leadership table. That's where we support hospital strategy, including equity, diversity and inclusion, decision making, operations, staff health and wellness, and respond to the most complex issues that hospitals face, like the pandemic.

The third is staying connected to our staff and our clients and families. The more layers that leaders have between themselves and the people doing the work and our children and families, the harder it is to be effective. I make a lot of effort to be out there to have conversations. I have built invaluable relationships with our client and family and youth leaders, and I would not, and could not, do any part of my job without them.

BLOOM: What's the greatest challenge?

Diane Savage: I think the biggest challenge is supporting our leads, the managers, to be able to do what they need to do and want to do. Those individuals have enormous roles to play and carry a lot of responsibility every day for the organization.

BLOOM: What qualities do you need to best support them?

Diane Savage: I think to listen deeply to what their experiences are, what their concerns are, and what they need as individuals to be able to thrive in their role. It's creating a space where they can come with all that they carry to talk openly—not only about what matters to them but how it impacts them and how I can help.

BLOOM: What's the greatest joy?

Diane Savage: Our partnership with kids, youth and families. It's being side by side with them every day. I am with them—in the elevators and our programs and in the concerns that get raised that I have the opportunity to help address. That is, for sure, the greatest joy of this work.

BLOOM: What emotions come with the job?

Diane Savage: Exhilaration, pride, hope, determination. Sometimes there are also emotions tied up with wishing I had done something differently, gotten it more right, or been more helpful. Those are hard and I've learned a few things that can help. One is being honest with myself if there's something I could have known and done better. I think it's probably taken my whole career to be able to quickly say yes, that is something that you missed. And to forgive myself sooner.

We all do the best we can and we still don't feel like it's good enough. There's a bit of self-talk that develops over time. Did I do the best that I could do? Did I intentionally cause hurt or harm or let somebody down? I can honestly say that's not the answer I come up with.

Part of it is that everyone in health care has such high expectations of themselves, me included. We're looking at our kids and families and staff and we just want to get it right as much as we can, and we do.

Given a particular situation, I encourage my leads to assess if there is anything they wish they had done differently. Usually they're very hard on themselves. I see my role as a leader to ease that burden of self-expectation, of perfection, because perfection isn't the goal.

Often there are factors that are both within and outside our control. Sometimes, honestly, we sit together and say how awful something is that has happened, and there may not be anything we can do to fix it. Leaders carry these things with them. I hope I create space to just sit together within that.

BLOOM: One of your colleagues noted that you have such an innovative mind, and wondered how you stay creative when you face so many systemic barriers to change?

Diane Savage: Wow, that's a lovely observation. I always think something else is possible. I always think that together we have the capacity to solve issues. I am a realistic optimist. When I retire, my first Twitter hashtag is going to be #positivelysavage!

That mindset enables me to see possibilities and hope. I trust in the talents of the people that I work with and that exist in this organization. We have created positive change together. I wish it would happen faster. There are some things it's going to take many lifetimes to change.

One area where we saw the opportunity to do more was in incorporating social determinants of health as an important consideration in how we support families. For example, we have a screening tool that asks parents about whether they eat less because they can't afford food, are worried they won't have housing in the near future, or have had to go without health care because of the cost. Families with urgent social needs are seen in our Family Navigation Hub so they can be linked to community supports.

BLOOM: I understand you're interested in coaching, and you have drawn on ideas from diverse sources. What qualities are important in a coach?

Diane Savage: Finding the right blend of supporting people's strengths and sharing opinions, direction and ideas, when they're requested. It's a two-way dialogue. People who come for coaching actually want to know how did you learn what you learned? They want to know if you've experienced some of the pitfalls they're experiencing, and how you navigated them.

It's important as a coach to help people see strengths in themselves that they may not see. And I strive to provide honest feedback. I listen for openings in a conversation to share things that can be hard, always balancing feedback with ideas and opportunities.

From a very young age, for whatever reason, I have tried to build skills in sharing difficult information in ways that can be heard, and I hope that contributes to people trusting me.

Caring Safely, our new high reliability framework, says, 'See something, Say something,' and I agree with this.

I'm a die-hard Toronto Raptors fan and Nick Nurse admirer. He knows how to support his team in and out of the skills and technique of playing basketball. I recently joined a three-hour basketball coaching session open to the public with a range of professional coaches, including Nick Nurse. I signed on, and learned there are some great similarities across every kind of coaching.

One thing Nick said at the end was that some of the hot shot players that they work with are very ambitious and they very much want to progress in their careers and to win. These are things that a coach wants, too. But sometimes it means someone is not a very good team player. Nick wanted to support them in their ambition and he said doing that was what helped them become part of the team. He had to figure out where they had common dreams with other players, not to deny them.

Another thing that helped me was some Second City training in improv I did many years ago. One improv term that will stay with me forever is to use 'Yes, and' and not 'Yes, but.' Improv teams create trust in each other by making space for people to create in the moment. If you're going down a sketch path and you say something with a dead stop, like 'Yes, but' it shuts down the ability for the flow.

BLOOM: So when you say 'Yes, but' you're shutting down an idea?

Diane Savage: Anyone who's ever had someone say 'Yes, but' feels like they haven't been heard. I believe I've incorporated that philosophy into my work.

BLOOM: What role here have you most enjoyed?

Diane Savage: I've had 12 incredible years here. I feel like I've always been here. I got an immersion from my early team in Participation and Inclusion about what matters. It was services I was less familiar with like therapeutic recreation, life skills, transition, music, art, aquatics, and communication and writing aids. It really helped me understand what Holland Bloorview is. One of our great contributions together was evolving a much more holistic and strengths-based definition of rehab.

In my role as VP of programs and services we were able to drive very exciting and innovative initiatives such as our Always Experiences—aspects of care that we must perform for every client, every time—as well as our work with the social determinants of health and so much more.

My recent role was designed to further integrate clinical practice and research, advance health equity, bridge client experiences to adulthood and build shared partnerships in the community to increase access to meaningful services for kids, wherever they live and whoever they are. The pandemic has impacted the pace of that change, but not our commitment.

BLOOM: If you could change one thing about children's rehab, what would it be?

Diane Savage: Maybe the term rehab. I've been thinking a lot about holistic care and the great work we've done to have children and youth be much more central in the way we shape our services, and to de-medicalize them. We know through our partnerships with kids and families that we're not here rehabilitating kids and youth. We're offering a range of exceptional, tailored programs and services as they go along in their life, based on what they need at different points in time.

BLOOM: Rehab does tend to connote a return to normalcy.

Diane Savage: And that's not what we mean here. I'm not sure what the right next language is, but rehab sounds limiting to me, and we are the opposite of limiting.

BLOOM: If you could go back and give yourself advice on your first day here, what would it be?

Diane Savage: Have faith, you are in the right place.

I've been lucky enough to have people help me be the leader I aspire to be with advice about what I needed to learn, understand, and value. Staff, families and leads have set me straight on more than one occasion!

I learned so much from those tough conversations. These were truth-tellers. It's important to surround yourself with people who will tell you the truth, not what you want to hear. You may not agree, and it may not work out in the way everyone hopes, but people have to know they can tell you everything they want to tell you.

I've said this is the best place to be and the hardest place to leave.

BLOOM: Is there anything we haven't talked about that's important?

Diane Savage: Something I think is so fundamental to who I am is having a sense of humour. I take great joy in finding things that are funny. I love comedy and stand-up and the craft of humour. I really work hard to bring a sense of humour and light to my team and to the work we do.

I was trying to understand why this is so important to me. I think it's because humour, being able to stand back and appreciate the absurdity of things, the joy and the pain, is about perspective. If you can find something that lifts you and others up, it means there is hope. Maybe it helps me and others do the hard stuff.

More than anything, I want to honour everyone that's here.

Like this interview? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter. You'll get family stories and expert advice on raising children with disabilities; interviews with activists, clinicians and researchers; and disability news.