For one mother, the key to positivity lies in intentions

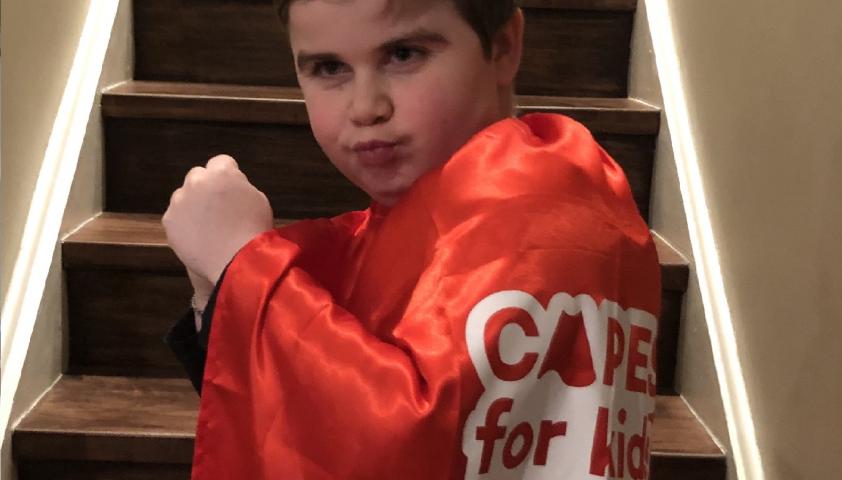

If you ask Kadey to describe her son Emery, she opens up by telling you he’s a character. While she’ll mention his passion for drawing and love of swimming, first and foremost Emery has a contagious laugh.

Whether he’s going out of his way to put a smile on your face or chuckling to himself in a corner of a room, there’s not a day that goes by without Emery bringing such joy.

And while the pre-teen is quick to crack a joke, he’s even quicker to stick his nose in a book to study the anatomy of an octopus or explore the expanse of space.

“He likes the idea of going into space. I think part of that is the discovery aspect, the scientific development, and also no gravity,” Kadey says.

“Because gravity and boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) are not really friends.”

The day it all changed

When Emery was a toddler, Kadey noticed that unlike her first-born, Lily, Emery wasn’t a talker, walker, or jumper. He didn’t crawl and he didn’t roll.

When she brought him to the doctor, occupational and speech therapy were recommended to help him along, while also being told that there was nothing wrong neurologically.

With lots of OT and ST help, eventually Emery took his first steps and shared his first words when he was almost three.

But just before his fifth birthday, after complications from an appendectomy, everything changed.

On Family Day in 2012, Emery was diagnosed with DMD.

DMD is a neuromuscular wasting disease where a child’s body doesn’t make dystrophin, which protects muscle cells. As Kadey explains, as children with DMD use their muscles, they break down—even through talking, walking, chewing, and breathing—and their muscles can’t grow back.

“Boys, often by their teenage years, are using a wheelchair quite a bit, if not for their overall mobility. And then they also need help with breathing in their late teens and early 20s, starting at night and then all the time, because the muscles that help with the breathing process also waste,” explains Kadey. She also adds that “of course, the heart is also a muscle.”

“DMD is considered a terminal diagnosis. When Emery was first diagnosed, we were told that the average life expectancy was 20. But now he’s 12, and we’ve been told we can expect Emery to live into his 30s, which in 7 years feels like tremendous improvement.”

Since that day, Emery—who at the time was in JK as part of Bloorview School’s integrated kindergarten program—began visiting Holland Bloorview to help manage his diagnosis. Every six months, Emery goes to the clinic to get assessed and to measure his function. The goal is to keep Emery mobile with good range of motion and a strong breathing capacity for as long as possible.

There’s no treatment for DMD, but medication helps slow it down.

Getting the right support

As for Kadey, she finds her emotional support through many different sources, including the support group at Holland Bloorview and friends she’s made who are also raising boys with DMD.

“The sessions are held six times a year and I’ll learn more in one session than I could possibly teach myself online,” she says. “I’m also there with other parents and, while you would never want anyone else to have to go through this, it really is important to have your community to know and feel that you’re not the only one.”

Part of managing the disease, the stress, and all the unknowns, is made a little easier because she writes down any questions she has—even at 3:13 a.m.—to help assuage her concerns.

“My husband, Marcus, and I built a binder at the beginning and put a pencil case, dividers, and a hole punch in it. Every time we go to an appointment, we bring our questions and write down everything. It helps us feel organized with tons of information” she says.

“We also always go to Emery’s clinic appointments together, which is not something all families can do, but bringing a family member or a friend to the appointments can help to listen and record information, even to prompt questions.”

It’s about living with intention

Kadey is hopeful that science is moving in the right direction with more research toward treatments, and hopefully one day a cure.

“Holland Bloorview has just started its own drug trial to treat DMD and part of this is because of the funding that’s been gathered through the Biggar Endowment for Muscular Dystrophy,” says Kadey.

“Since Emery’s diagnosis, a bunch of my friends in my industry started Music Heals. We just had Music Heals 8 in June, raising more than $330,000 in eight years.”

It’s that same energy, optimism, and drive, that also helps Kadey and her family move forward.

“You have this child who’s magnificent—and to be perfectly clear he’s still completely magnificent—and then his life, your life and everyone’s life, changes in a moment and there’s nothing anyone could have done differently to change the diagnosis, so it's you who must change,” she says.

When asked about her advice to parents who have other kids who do not have DMD, “This diagnosis does not ruin your other children. I feared it would. But, like with Lily, it can make them stronger and kinder. We never know what life is going to bring. DMD makes us know that it’s not going to bring forever, in a very concreate way. DMD makes us more intentional in the moment, perhaps even optimistic.”

Quick Facts about Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

September is Muscular Dystrophy Month and September 7, is World Duchenne Awareness Day. Here’s some more information to better understand this diagnosis.

What are the first signs of DMD?

Most children with DMD won’t be diagnosed until they’re around 3 or 4. Symptoms can include:

- Muscle weakness that starts in the hips, pelvis, and legs

- Clumsiness and falling often

- Unsteady, waddling gait

- Difficulty standing

- Trouble learning to sit independently/walk

How common is DMD?

DMD occurs in approximately 1 of every 3,500 male births. It is usually determined between the ages of 3 and 5.

Who is affected by DMD?

DMD mainly affects males—rarely does it affect females. This is because the DMD gene mutation is in the inherited X chromosome. Females have a second X chromosome that is healthy enough to produce enough dystrophin to protect the child from DMD. While rare, it is still possible for someone to develop DMD even with parents who don't carry the mutation. This occurs in approximately 30% of cases.

How is DMD diagnosed?

A doctor can diagnose DMD through a variety of tests. These can include:

- Testing the blood for the enzymes released by damaged muscles

- Genetic testing to see if there is a mutation in the DMD gene

- Performing a muscle biopsy

How is DMD treated?

While there currently is no cure for DMD, treatments can help control symptoms to improve quality of life. Steroid drugs can be used to help slow down the muscle wasting. Similarly, many different research initiatives and drug trials are underway to change the course of this disease.