A boy without speech conveys a world of emotion

By Louise Kinross

A Day With No Words is a stunning book out in May about a boy who loves to hug trees, eat fries, and dance barefoot in the grass. It’s written by Tiffany Hammond, an autistic writer who is homeschooling her two autistic sons in Texas. The story is a “love letter to Aidan,” her 15-year-old son, she writes, and follows a day in the life of a mom and son who communicate with iPads. Their bond is palpable. Tiffany is the creator of Fidgets and Fries, where her writing on family life and autism reaches over 27,000 followers. The exquisite book illustrations are by Kate Cosgrove.

BLOOM: Why was there a need for A Day With No Words?

Tiffany Hammond: Because I didn't see anything like it out there. There weren't many children's books that had Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC) characters in the first place, and the ones that talked about disability were very stiff. They were mechanical, like: 'This is Sally. Sally has a disability. Sally doesn't walk and uses a wheelchair.' While we liked those booked because they introduced our children to that world, to people with different disabilities, they didn't have disabilities like my boys.

BLOOM: Can you tell us a bit about your son Aidan?

Tiffany Hammond: He's 15 and non-speaking. He doesn't say any words and he communicates right now with an iPad with Proloquo2Go. We just got the new version. We're also trying to teach him spelling with Spelling to Communicate, to open his world up a bit more.

He's generally a pretty happy person. He loves his fries, music, especially Rihanna, trees and car rides.

BLOOM: I read on your website about how you can read Aidan in many ways.

Tiffany Hammond: Yes, through his body language: How his eyes look and how his shoulders sit and how he touches you and even different types of grunts he makes, we know okay, this is what he's trying to tell us. The way he moves and the sounds he makes and the pitch of those things. What's complicated is that we can read him decently and well, but everyone outside of us can't. So we need to help him find his best way to communicate with his world.

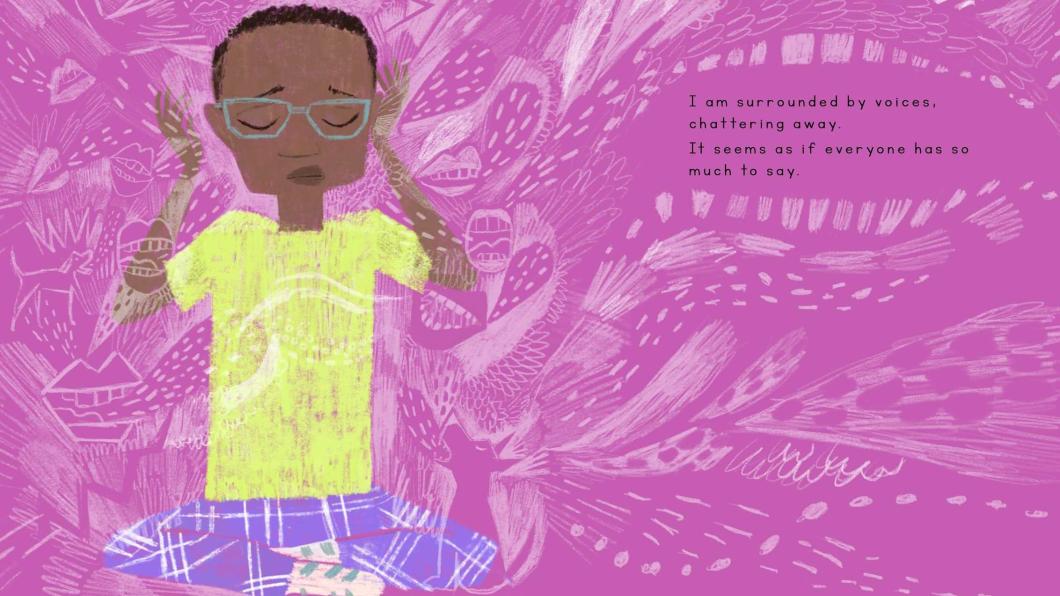

BLOOM: There's a moving passage in the book where the boy talks about being surrounded by voices, but he's shut out. What have you learned about the value our culture places on speech.

Tiffany Hammond: I learned that it's pretty much everything. Even though we spend the bulk of our day on social media, not talking but communicating back and forth, or we send an e-mail, or we can look at each other with a look, and know what the other person means, we still value speech so much. We find it more convenient. It's quick information.

When we go to the store the staff is impatient waiting for my son to use his tablet to ask for candy. Even at drive-throughs, where they say if you have a hard time reading the menu pull forward and we'll give you a special way to communicate, even when you do that, they act like you have three heads. Nobody is willing to wait.

BLOOM: The demand for speed is intense.

Tiffany Hammond: It's sad. It doesn't take much for this world to be more accommodating. People choose not to. It's an active decision. They're deliberately choosing to not be accommodating.

BLOOM: In the book, the mother and son take iPads with them and use a voice app to communicate when they're at the park or ordering food at a restaurant. Why do you use the tablet when you can speak?

Tiffany Hammond: It started with my youngest son Josiah. He also has autism and one day he said: 'Why don't we talk like Aidan talks?' Then we learned having multiple people use devices was called modelling. So we were showing Aidan how to use his tablet by using ours. My husband does the same.

You sit there and you think, how would it feel to talk with someone and when you're done they take your mouth and use it to talk back?

We used to use the tablets just at home, but when we started to go outside with them it was a whole new world. It was challenging to learn how impatient people can be.

We're in a small town and you go to the same stores. One day you see someone and they know you were talking yesterday and now you're not. Some people are kind and others are not. There's never a time we go out when someone doesn't say something about my son, and a lot of times you want to say something back but most of the times I don't.

When I feel I need to say something, I can't use my words, and you're so mad and frustrated and want to explode from the inside out. There's only so much you can say with pictures. That's when you go 'Wow, this is what Aidan goes through every day. To not be able to say what you need to say.'

I can't completely put myself into his body, but I try to get as close to it as I can and I use that to inform the advocacy that I do.

BLOOM: It seems odd that if you're in a small town and everyone is used to seeing your family they wouldn't get with the program and understand. In your book, the boy is ostracized by a mother and kids at the park. Where does Aidan feel safe and heard?

Tiffany Hammond: With us. Home is always the safe space. It's sad that it's the only place. There is no place we go where people don't make comments. When Aidan was in school, he was the only one like him, whether we were in a town of 5,000 or 140,000. He was with other kids with disabilities, but they all spoke. Even in that classroom, he was different. You hear a lot and you see a lot and I know if I'm hearing this stuff he's hearing it.

Five years ago we began homeschooling. I pulled out his brother as well. It's a lot of work, but it's better and depending on where you live, there's sometimes a good homeschool co-op that tends to be understanding. There are a lot of families like ours who choose to homeschool.

Aidan is an amazing person but a lot of people don't take the time to know him or understand him.

BLOOM: The bond between mother and son is so palpable in your book. How have you changed as a person through raising Aidan

Tiffany Hammond: I like to think I've grown a lot in patience and recognizing the things that really matter. I'm learning to prioritize different things. I'm being more patient and being more mindful and living more of my life like Aidan does. He's very free. He's carefree. He doesn't mask. He's very open. I'm trying to help him see the beauty of who he is and in doing that recognizing how awesome I am as a person and a parent, and how hard that I do try. I try to be a better person. I think both of my kids help me to be a better advocate and storyteller and I'm inspired by them a lot.

BLOOM: How does being autistic influence your parenting?

Tiffany Hammond: Having the same diagnosis helps me to have a different perspective of a situation. I don't jump to 'Wow, that is a behaviour issue we need to fix.' Instead I'm thinking 'There's something else going on here, that underlies this. What else could it be? Could this be sensory, or is there a medical angle?' Nothing is ever straightforward. I think that helps a lot.

In other ways it's very difficult for all of us to exist in the same house because sometimes we trigger each other. We need to co-exist without launching each other into a meltdown. It's trying to find that balance.

There aren't many families like ours around me. Most of my connections are online. I have connections with other parents who don't have autism, and with other autistic people that don't have kids. I try to learn from every person. This community is very divisive. You have the autistic adults and you have the parents, and it feels like a war. I don't want to be in any of that. I want to help people and I learn from and value everyone.

BLOOM: What was most challenging about writing the book?

Tiffany Hammond: That it had to be 600 words or less. I thought how am I going to put all I want to talk about in 600 words?

BLOOM: Why 600 words?

Tiffany Hammond: It's a children's book thing. Publishers don't want you to make it too long. The best thing about having an editor was being told to overwrite it, and then we chopped it down. You don't want kids to lose interest and you want them to pay attention from the start to the finish.

BLOOM: What does Aidan think of the book?

Tiffany Hammond: I only just got a hard copy, so we haven't read it to him yet. I'm waiting for the perfect time. I want to add buttons that look like some of the images to his Proloquo. So he can interact with it.

I've shown him the cover and he stares and smiles at it a lot and touches it. He knows it's him.

BLOOM: What do you hope children take from the book?

Tiffany Hammond: My target is child readers and the people who read to them. A lot of the time that's parents, teachers, therapists and librarians.

The park scene in the book was super important because it involved parents and I wanted to highlight that. My son was the only one like him at school, so this book might be a child's introduction to the world of disability. They may not have seen it yet. I wanted it to be something that would be memorable to them and give them something they can do.

When Aidan started school the other kids were curious and they played with him, even if he didn't completely play back. But by Grade 2 they changed. After the summer it was 'He's so weird,' and 'I don't want to sit with him' and 'He's scaring me.' I'd like to catch kids with this book before they start treating other kids the way they treated Aidan. Hopefully the book will help kids to understand it's okay to be different.

Learn more at A Day With No Words. You can pre-order or gift a book to a school or library. Like this interview? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter. You'll get family stories and expert advice on parenting children with disabilities; interviews with activists, clinicians and researchers; and disability news.