Autism is at the heart of an Irish teen's dazzling memoir about nature

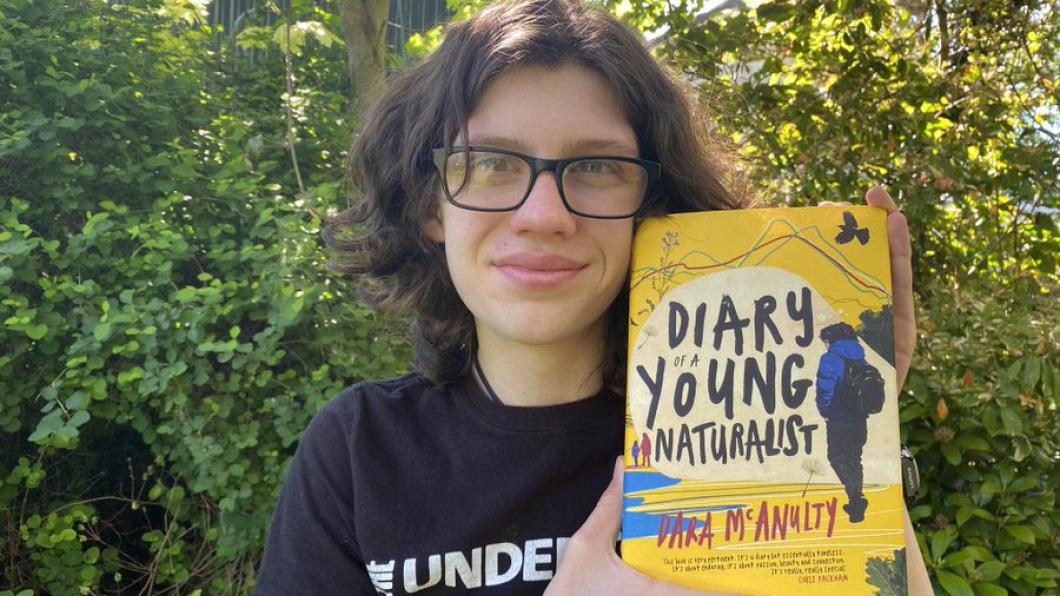

Photo @naturalistdara.

By Louise Kinross

Diary of a Young Naturalist follows author Dara McAlnuty through the four seasons of his 14th year, when his family moves from one side of Northern Ireland to the other, leaving a beloved forest to settle in the Mourne Mountains.

The book is as much about autism as it is about nature and wildlife. It bursts with vivid descriptions of creatures great and small, reflecting Dara's deep emotional connection to the natural world, acute observation, and photographic memory. “The camera clicks in my memory and there it will stay, like all these moments,” he writes. “Catalogued. Picture perfect.” Later, he retrieves the images and translates them into words. “The intensity gushes out and I feel everything again...I don't need to think about it much; all the details are right there in my mind and it surprises me every time. And high up here I'm not thinking. I'm feeling, observing.”

Reading this book made me want to see and understand wildlife—even insects, which I never liked before! Here’s Dara's elegant account of a water boatman: “The oar-shaped hind legs are still outstretched, resting on my bright-blue fleece as if it were the surface of a pond.” Other images lodged in my mind include the whooper swan with its rotating “webbed paddles” on takeoff; the puffin who waddles on land “yet can reach 55 mph by manically flapping four hundred times a minute;” and the swift that just arrived direct from Africa. And I will never forget the “tiny orange microdots” Dara spies on the green stalk of a cuckoo flower. They are eggs, deposited by the orange-tip butterfly.

Dara’s family is a tight group bound together by two things: their passion for nature and autism.

A day doesn't pass without a walk to the beach or forest, and the family frequently hops in the car to drive to nature reserves and wilderness spots. It may be for a day or an extended stay.

Dara, his mother and two siblings are on the spectrum, as is Rosie, a retired greyhound who insists on walking the same routes. Only Dara’s dad, a conservation scientist, is neurotypical. “We’re as close as otters, and huddled together, we make our way in the world,” Dara writes.

For Dara, watching nature is medicine for his brain. “…Outside the world is so much easier to condense and understand,” he writes. “You can focus in on one thing: a flower, a bird, a sound, an insect. School is the opposite. I can never think straight. My brain becomes engulfed by colour and noise and remembering to be organized.”

Diary of a Young Naturalist is a fascinating window into what it’s like to be autistic in a neurotypical world. “Autism makes me feel everything more intensely: I don’t have a joy filter.”

Dara's intensity is viewed as decidedly uncool at school, and bullies torment him. Hiding who he is to escape ridicule is a daily ordeal. He likens it to the movement of a duck on water: “We rarely think of all that effort being made below the water, those webbed propellers whirring so the bird can glide with such ease and grace on the river. It’s just like being autistic. On the surface, no one realizes the work needed, the energy used, so you can blend in and be like everyone else.”

Dara's autistic mother is an anchor in his life, interpreting the social world around him. “Every day, ever since I can remember, Mum has sat me down, sat us all down, and explained every situation we’ve ever had to deal with. Whether it was going to the park, to the cinema, to someone’s house, to a café. Every time, all manner of things were delicately instructed. Social cues, meanings of gestures, some handy answers if we didn’t know what to say.”

A particularly moving scene involves their arrival at Rathlin Island, Northern Ireland’s largest seabird colony, which is swarming with people. “…Before we head down to the viewing platform, Mum takes me aside,” Dara writes. “We exchange code words and hand squeezes. I build an imaginary suit of armour around myself and move forwards into the throng…”

There’s a brilliant passage in the book where Dara describes autistic “stimming” in his family. “Lorcan uses sounds, squeaks, grunts, purrs, whistles, groans. Bláthnaid twirls her fingers, hand-flaps and makes sucking-in noises which she calls ‘fluorescent stress-taking movements.’ It’s not weird. It’s just different. Some neurotypical people talk incessantly—so much small talk! I curl my hair, jump randomly and sometimes, embarrassingly, do a few wiggles. I control it when people are around. Lorcan is beginning to stifle it when others are around. Bláthnaid, because she’s younger and less self-conscious, is an unbridled stimmer. But so what? It’s who we are. It’s how our happiness bubbles out, and how our anxiety seeps. It’s just how we regulate our brains. You probably stim too, without realizing. Ever bite your nails? Twirl your hair? Pull at your ear?”

Educators could learn a lot from his description of a nurturing school environment. “My idea classroom would have no bright colours and lots of natural light. It would have a single line of symmetrical windows, six feet off the ground, looking out to sky and birds. The space itself would be cozy, and the desks would be arranged in a horseshoe, not a circle. I’d sit in the middle, at the bottom of the curve, so I could place everyone but not have to look straight at them. There would be nobody behind me—I need to know what’s happening all around...”

Diary of a Young Naturalist is filled with fascinating history of the natural world and our connection to it. For example, “A bluebell wood takes much longer than our time on earth to get to this carpet of bloom,” Dara writes. “It is precious and ancient and magical. And it arrives like clockwork, if left alone, casting a charm on so many open hearts. Here since the Ice Age, the bluebell takes five whole years to grow, from seed to bulb.”

Of dragonflies he writes: “...their silken wings etched with the maps of the Carboniferous (their wings spanned six feet when their ancestors flew with dinosaurs). They zoom still, like turbo-boosted flecks of light, wings catching the light and showing us glimpses of eons past.”

Over the course of the year, Dara becomes an environmental activist. He gives speeches, writes articles and walks out of school with Greta Thunberg and students around the world to demand action on climate change.

"Globally, we have lost 60 per cent of our wild species since 1970,” he writes. “And it's my generation that is labelled 'apathetic,' 'self-indulgent,' 'less focused!' Whereas the adults, who are actually in control of our access to wildlife, the boundaries between busy roads, housing developments and green spaces, carry on making decisions and spending public money in conflict with nature.”

Diary of a Young Naturalist is written in the present tense. Its message is personal and urgent. “It's my duty, the duty of all of us, to support and protect nature,” Dary writes. “Our life support system, our interconnectedness, our interdependence.”

To learn more about Dara and his conservation work, watch this video. Diary of a Young Naturalist has been short-listed for the 2020 Wainwright Prize for UK Nature Writing. It's published by Little Toller Books.