Telling clinician and patient stories increases empathy in nurses

By Louise Kinross

A six-week narrative group for inpatient nurses at Holland Bloorview promoted greater empathy for patients and families, for each other, and for the nurses themselves, according to a study published in The Journal of Pediatric Nursing last month.

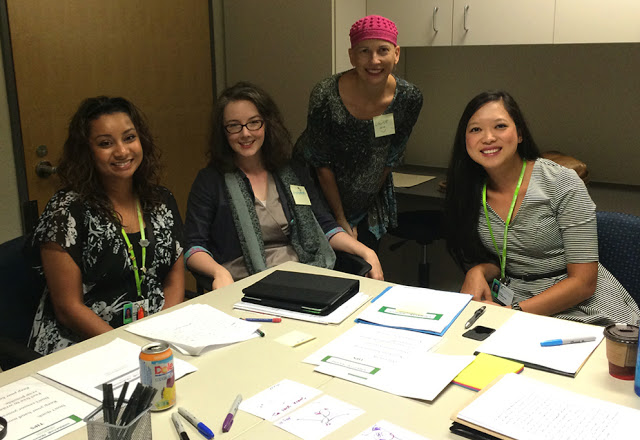

I was a facilitator on this project, which was led by Keith Adamson, then collaborative practice leader at Holland Bloorview. The other facilitators were Andrea Charise (photo centre left), who directs an undergraduate health humanities program at the University of Toronto, and Shelley Wall, a medical illustrator and assistant professor in Biomedical Communications at U of T. Sonia Sengsavang (photo right), a PhD candidate in developmental psychology, was research assistant and Michelle Balkaran (left), a nurse and now an interim operations manager here, was part of the research team.

I will write pieces on each of three areas where the group was shown to improve empathy. The first was empathy for patients and families.

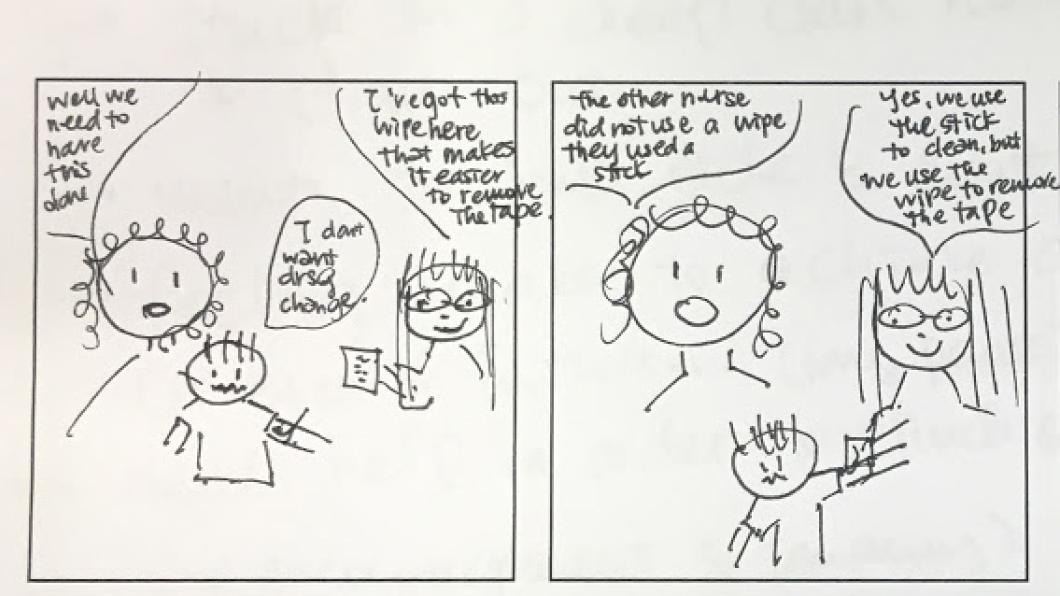

Each 90-minute session began with reading of a patient story, poem or comic that addressed common themes in children’s rehab such as ‘Seeing from different points of view;’ ‘Obstacles to empathy;’ and ‘Making room for hope.’

Facilitators led a discussion of the reading, then gave participants a related writing or drawing prompt. For example, ‘Write about a time that you received care’ or ‘In a three-panel comic, tell the story of a patient through their parents’ eyes.’ Participants then shared and discussed their work.

In the study, empathy is described as “The capacity to imagine the situation of each patient and their family—understanding their feelings and perspective, and responding in ways that make patients feel heard and cared for…”

Participants, from each of Holland Bloorview's inpatient units, worked with children hospitalized following painful bone surgeries or life-changing trauma, such as brain injury, or with complex medical problems. Each nurse did an in-depth interview before and after the group.

Prior to the group, nurses expressed a desire to understand the family’s perspective, but often in the jargon of patient and family-centred care, the study found. For example, they “partner” with the family, and “Think of yourself being in their shoes,” but don’t give specific examples.

After the intervention, participants described a new understanding that every family has a unique backstory—the complex, often painful experiences that occur before and during the current care episode. This backstory guides concrete ways to express empathy, through kindness, listening, being aware, flexible and patient, trying not to judge, and giving the family the benefit of the doubt.

“These stories helped me think, Okay, this is a young girl,” one nurse said. “She misses her mom. Let’s just take five minutes.” Another said: “trying not to be so quick to judge things and to listen better.” And another: “On Tuesday when I was doing a port needle with a patient who has cancer…I [thought], ‘oh my goodness they are sick for a long time and it seems, like never-ending’…that insight that I got from the comic…it’s like ‘Yea, this must be really hard in their life.’”

Along with this new recognition of the complexity and fragility of families comes the understanding that nurses’ words and actions have tremendous power to help or harm.

Prior to narrative training, participants described a tension in balancing “direct nursing”—their medical tasks, procedures and documentation—with providing emotional support. Given time pressures and the expectation to maintain professional detachment, they prioritized technical tasks over emotional support, describing the latter as “outside my nursing hat.”

After the narrative group, the nurses elevate compassion, listening, being flexible and providing a safe space to families, as being on par with direct nursing tasks. For example, “Yes, we do the technical stuff but we feel like we’re so much more the emotion, the support, as well,” one said. And: “Really taking that time to sit down, as we were experiencing in the six-week [intervention], right? Give them a safe space.”

Nurses also reported being more likely to share personal information if they felt it would help them connect with families on a human level. “Sometimes telling [patients/families] something about your own life may put them at ease or help them relate better to the situation they’re in.”

The researchers coined the phrase moral empathic distress (MED) to describe a new, emerging concept in rehab nursing. “MED can be considered an internal state associated with nurses’ feelings of profound helplessness, which emerges when nursing interventions are unlikely to alleviate a pediatric patient’s physical pain or chronic condition,” they wrote. This was heightened in rehab because clinicians develop relationships with children and families over months to years. Pre-intervention, nurses described this dilemma: “It’s more like picking up your own child, right?” said one participant. “So when we see suffering it’s more disturbing.”

After narrative training, participants were more likely to recognize that when there is no medical solution, their emotional presence with patients and families was invaluable. “Maybe there’s nothing more we can do, but… what I’ve learned is just to be present for the family and be their support,” said one. “And to hold their hand and to tell them, ‘Cry and be mad, because that is normal—you’re going to grieve.’”

Through storytelling, participants learned that their peers all experience work-related emotions like regret, grief and helplessness. Knowing that they were not alone in these emotions helped them cope. “One of the other [nurses]…was reading her piece and taking about how her patient was in pain and she was trying to help and it’s not helping,” one participant said. “And in the intervention she’s crying. You know, seeing how it’s not just me who gets really emotional and thinks about it—it’s other staff too.”

We'll explore how the narrative group increased empathy for participants' work peers and themselves in future posts.

This project was funded by a Catalyst Grant from the Bloorview Research Institute.