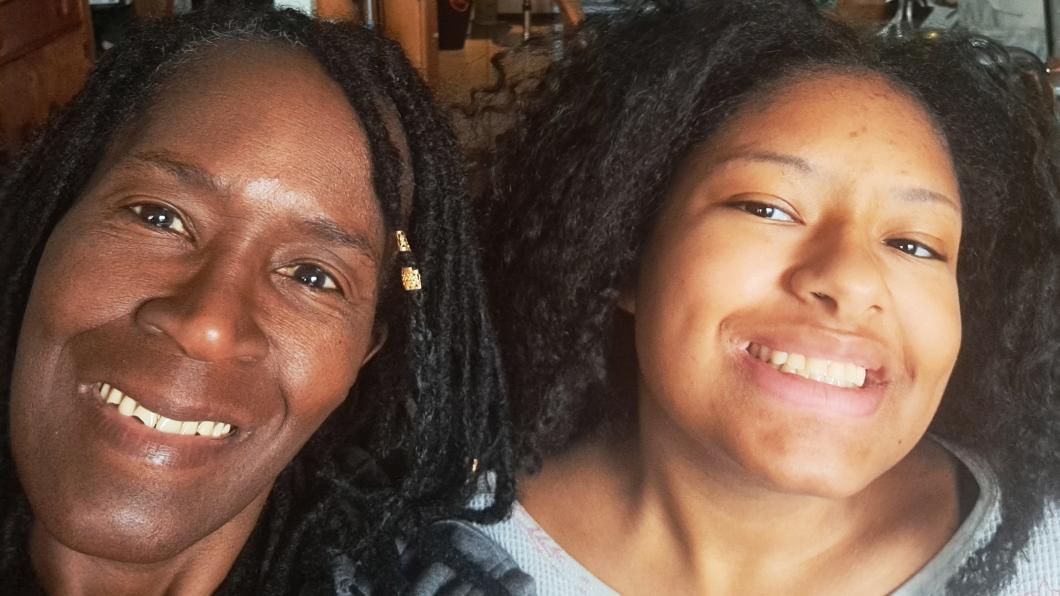

Mother fights anti-Black bias in autistic daughter's care

By Louise Kinross

Numerous studies show racial bias in health care. For example, Black children receive autism diagnoses much later than white peers, and Black children are less likely than white children to be given pain medicine when they visit an ER for a broken bone or appendicitis.

Nerissa Hutchinson has seen anti-Black bias play out in the care her daughter Fallon received since she was a young child. She says it's the reason Fallon wasn't diagnosed with autism until age 13, and with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis until she was 15.

Fallon recently completed Holland Bloorview's Get Up and Go program, an inpatient program for youth with chronic pain. She just turned 18, and has struggled with joint pain all her life. Last year she rated her pain 10 out of 10, slept 18 to 20 hours a day, and had stopped going to school.

When she was younger, the pain caused her to fall a lot, but doctors dismissed it as "growing pains," Nerissa says. They ridiculed Fallon when she used a cane, saying she was faking it to get attention. Later, doctors berated Nerissa when she brought Fallon to the ER multiple times because she was so stiff she couldn't move. "Weren't you here a couple of days ago?" they asked. "Why are you still here?"

"What I was coming up against in the health-care system was not being heard, not being valued, not being seen and acknowledged," says Nerissa, who is a child and youth care practitioner doing her Master's in counselling psychology at York University.

The same pattern played out when Nerissa raised concerns in preschool that Fallon was autistic. "We noticed certain behaviours, certain tics and stimming, but our family doctor said she didn't see anything and it's just the way she is."

Once in school, Fallon's behaviours were identified as defiance and "not listening" and the family was sent to a months-long program for non-autistic children with behaviour problems. "If she was a white girl, I think she would have been looked at differently," Nerissa says. "No one talked to us to really understand how we explained her behaviours."

Meanwhile, Fallon was bullied so terribly at school that Nerissa had to homeschool her from Grade 2 through 6.

When she was 11, a paramedic taking Fallon to the ER for pain told Nerissa "Your daughter is autistic."

"It was the first time someone started validating it," Nerissa says. She later sat in her family doctor's office and said she wasn't leaving until Fallon was diagnosed with autism. She was referred to another doctor in the same hospital and eventually assessed elsewhere. One clinician asked Fallon, then 13, to open her mouth, and showed her mother that she had raw, open sores on the insides of her mouth. She'd been biting down to try to prevent herself from stimming.

Unfortunately, receiving a diagnosis didn't result in many new supports. "I was on my own calling around," she says. "The programs were mostly tailored to families with young kids, but autism doesn't age out."

It was two years after Fallon's autism diagnosis that she finally received a diagnosis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA). It was another two years before Nerissa learned about the Get Up and Go program at Holland Bloorview.

The program involves two inpatient weeks and two daypatient weeks with a team that includes physical and occupational therapy, social work, psychiatry and the hospital's onsite school.

"They taught her to live with her pain and she was acknowledged and supported and for the first time they believed her," Nerissa says. Fallon benefited from the program's structured days.

"The first day they had a schedule, and she wasn't allowed to sleep in bed," Nerissa says. "There was actual physiotherapy, actual swimming, seeing a social worker and a psychiatrist and she had school. That's so important, because with JRA, if you don't move, the pain gets worse, so it's a vicious cycle. They got her on a routine and active, so by the end of the day she was tired, and she slept. She would tell me 'Mom, I'm having the best sleeps.' She was still in pain in the morning, but she had rested during sleep. Within a week, I see Fallon smiling, my daughter is happy, and she's sleeping at night. The pain is still there, but how she views it has changed."

When Fallon went to the day program for two weeks she was able to practise what she'd learned at home at night. "Now she's finished the program she may get up in the morning and say 'This is a bad flare up,' but she still gets dressed and goes to school," Nerissa says. "They taught her that if she has bad pain, she can still do some activity. Maybe she won't do full physio, but maybe she'll sit in her chair and move her leg. If she can't swim, maybe she can just wade around."

Nerissa says the Get Up and Go staff ensured the supports Fallon needed were at school when she returned. "For example, she's supposed to use the elevator, but she often couldn't find the person who had the key, so she had to take the stairs. I'd been advocating to the principal about it, but it wasn't until Get Up and Go got involved that someone is there everyday for her with the key."

Fallon is again talking about her future as a marine biologist, something which felt impossible just a few months ago.

Nerissa says the Get Up and Go program has provided the best support for Fallon's pain.

When it comes to autism, Nerissa did a lot of her own research and also became part of a Toronto support group for Black parents of children with disabilities (See our BLOOM story. The group is now known as Sawubona Africentric Circle of Support).

"I went to the first meeting online and everyone was Black and oh my God, they all had the same story about their kids being diagnosed at 13, 15 or 16, and how professionals interpreted their child's behaviour as defiance. So I'm not alone. I got so involved with the organization. I found a home and I'm now a board member of Sawubona." The group provides supports and resources to families of African descent in the GTA.

"With funding through Trillium grants we support families of children with disabilities through workshops, seminars, dads' and moms' support groups, speakers. We have a paint night where we provide the canvas, paint and materials for families to paint at home. We have a summer picnic and Christmas party and we work with TAIBU Community Health Centre, where Black families can get their children homework help."

Nerissa has advice for Black families earlier on in the process with their child with a disability.

"There is support in the school, but you have to advocate for it," she says. "You can get a psychological assessment for your child, but you have to keep at it to get it.

"Another thing I say is 'Build your community.' Reach out to organizations like ourselves and we can advocate on your behalf. We can support you. It's important to have a community that helps you, because it's a lot of work and you can't carry it alone. I am now on the Special Education Advisory Committee (SEAC) for the Toronto District School Board and I can advocate on families' behalf. I support a lot of families because I don't want others to go through what I went through."

When it comes to qualities Nerissa values in health professionals, "compassion goes a long way," she says. "Check your biases. Believe when a child or a parent is telling you something is wrong. Believe us."

Nerissa says hiring Black clinicians is one way Holland Bloorview could better tailor its services to the needs of Black families.

"As a Black family, when you walk into an environment that is predominantly white, you go 'Okay, which mask should I put on?' I can't be too loud, I can't come off as too harsh. How will I behave? You're gauging the professional's behaviour and learning how to respond. If you raise your voice too much you're seen as the angry Black person. When we see other Black health professionals we always nod or smile because it make you feel like 'I'm going to be seen.' When I walked into the Get Up and Go program I came in with 'I'm going to be a Black mama bear.' But when I left I was a little cub. I felt like I could be a little cub. I didn't have to be so hard."

Like this story? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter, follow @LouiseKinross on Twitter, or watch our A Family Like Mine video series.